The first time I realized the world outside my family’s walls was different—colder, stranger, and somehow louder—I was five years old. It was late Spring. I don’t remember what day it was, though days didn’t mean much then anyway. They were just spaces between the times when Baba came home from work or my brother had university classes.

Inside our house, life was wrapped in a kind of warmth that only families could make, secluded and protected from outside world. Baba’s voice was the loudest but filling the room like the radio’s evening broadcasts though he’s always been a very quiet person and Maman’s was softer, moving through the house like a breeze that carried smells of fresh broadbeans. Late Spring, meant we had to buy piles of broadbeans and get them out of the casing and later we’d have BaghaliPolo for dinner before freezing the rest. My world felt safe within those walls.

And then there was me, the observer, with my Batman and Robin Tshirt and a thousand questions that no one had time to answer like why the moon follows me where ever we go or why the Mullahs are always on TV. But More importantly at that stage, how do I make the Betamax player work.

We had two video players a VHS and a Betamax. They were locked in the closet hidden and I was not supposed to talk to the kids in the street that we had video-players. You see, having video-players and movies were illegal. Outside, the world had rules I couldn’t understand. Women wore black chadors moving like bats, but some other women like my mom never wore chador and wore a black scarf over their head and manteaux. This told me my mom was more progressive than the chadoris, or lots of men had beards and they were more angry. My dad always shaved, and he wasn’t angry, so he was again more progressive.

Outside our home, the streets were a different world altogether. They were loud, chaotic, and filled with smells that both fascinated and repelled me: diesel, freshly baked bread, fruits and sweat. The walls of buildings were covered in revolutionary slogans and black-and-white posters and colourful murals of young men who had died in the war. Their eyes seemed to follow me wherever I went, their smiles frozen in time.

Back to my Betamax question, I have the Robin Hood on Betamax and I want to know how to watch it, but I have to wait for my brother to come home from uni. My brother had a friend called Vesal, which is a Quranic name and means ‘reunion’ rightly so for this story.Vesal was our ‘dealer’. He had an illegal business of selling tapes, both music and movies. American music and movies to connect us to the world beyond angry bearded men and bat-like women who gave me gag reflexes as they always smelled. Just a few days ago, my brother had got Disney’s Robin Hood from Vesal and the dude that he was he even taped Michael Jackson’s Thriller at the end of the Betamax tape. What a cool guy! So I waited for my brother to come home and straight away annoyed the fuck out of him to bring the Sony Betamax player out and set it up. I hovered over him as he fiddled with the wires, biting my nails in anticipation. At one point, he shot me a glare so sharp it could have cut through the cables. “Go sit down,” he barked, which I did for exactly two seconds before bouncing back to his side.

Finally, the screen flickered to life. I’d never seen anything so magical: an animated fox with a bow and arrow, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. I was hooked. Robin Hood was brave, clever, and—most importantly—a fox. Maman even peeked in from the kitchen, a smile tugging at her lips as she saw me glued to the screen. And then, after Robin Hood’s triumphant rescue of the other animals from Prince John’s castle, he jumped into a pond and his hat floated on top but he didn’t come up. Little John and Lady Marian started crying and then the screen went black. It ended! Robin Hood died. I sat there, frozen, staring at the empty screen. My chest felt tight, my throat burned, and then the tears came. Big, hot, heaving sobs. Maman rushed in, alarmed. Baba leaned back in his chair, confused but trying to look understanding, as though this were a problem solvable by radio news commentary. My brother came to console me. A picture appeared and it was Michael Jackson’s Thriller. So Robin Hood did certainly die. And my brother was trying to distract me by directing my attention to Thriller.

“Look, it’s a music video. It’s Michael Jackson. Zombies and everything!” he said, his voice a mix of desperation and hope.

I blinked at the screen, my tear-soaked face contorting as I tried to process what was happening. I loved Michael Jackson but I now loved Robin Hood more. One minute, my beloved Robin Hood was a tragic hero, and the next, Michael Jackson was moonwalking with the undead scaring the shit out of me. It was too much for my little brain to handle. I sobbed harder.My brother groaned, rubbing his temples. “No! Robin Hood isn’t dead, okay? Thriller is just… something else, Vesal has taped over the ending. Robin Hood lives happily ever after’.

But deep down, the damage was done. For five years after that day until I watched the full version, I carried the heavy truth that Robin Hood was a tragic hero who sacrificed himself for love and justice. It didn’t matter that my brother tried to reassure me or that Maman soothed me with her amazing Baghali Polo. In my mind, heroes like Robin Hood were destined to die.

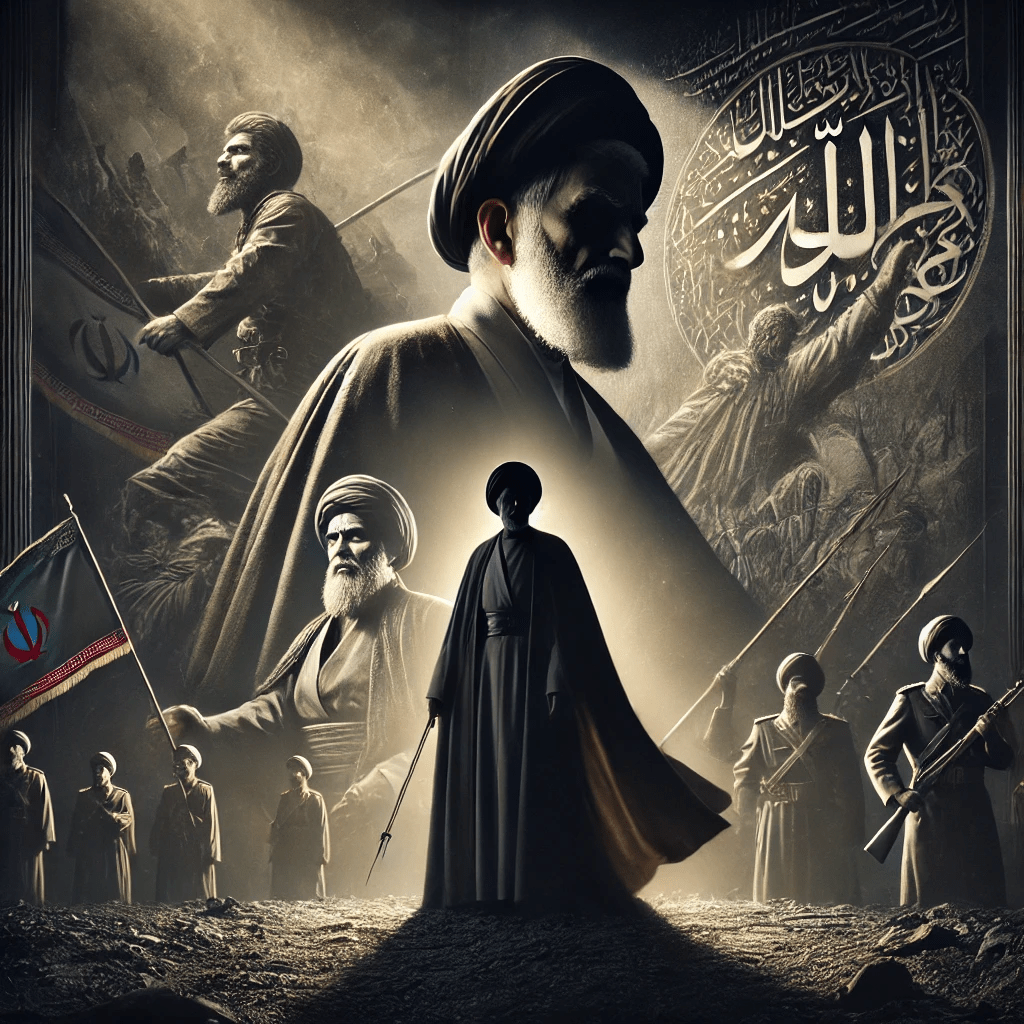

Looking back, it wasn’t so strange to believe that. I grew up in a world where tragedy wasn’t just in stories; it was everywhere. On the TV, the newspapers, the hushed conversations between Baba and Maman late at night when they thought I was asleep. Martyrdom was glorified. The murals of war heroes, often child soldiers—smiling boys frozen in their youth—lined the streets of Tehran like a second set of mournful billboards. Every child knew stories of warriors, sometimes even their brothers, who had died in battle, their faces forever etched into our collective memory.![[Pasted image 20241222144222.png]]

And here was Robin Hood, brave and selfless, pursuing the same path. It made perfect sense to me then. Aristotle called it the tragic hero’s arc: a great man, flawed yet noble, whose downfall was inevitable but meaningful. My five-year-old self didn’t know Aristotle, but I lived in a world that embodied his ideas. Martyrdom was not just a theme; it was a cultural cornerstone.

In Tehran, martyrdom wasn’t an abstract idea; it was embedded in the culture and politics that surrounded us. The posters and murals of war martyrs lining the streets weren’t just commemorations—they were reminders of the ideals you were expected to revere. These young men, frozen in time with their smiling faces, were held up as paragons of virtue. They embodied sacrifice, loyalty, and the ultimate devotion to a greater cause defined by the Islamic Republic, just as fascist regimes mythologize their martyrs to inspire collective unity and control.

This cultural framing made the idea of a heroic death seem not just normal, but inevitable. When Robin Hood appeared on your screen—a cunning, selfless hero standing against tyranny—it was natural for your young mind to slot him into the same narrative. If soldiers in posters, warriors in bedtime stories, and even Prophets and Imams in religious tales achieved glory through sacrifice, why wouldn’t Robin Hood follow the same path? Although completely arbitrary, for my 5 year old brain, this all made sense. His imagined death felt right, even if it was devastating. It fit the narrative that had been subtly built around me: that heroes must die to truly be heroes.

Even though Robin Hood wasn’t from my culture, his story resonated with the underlying themes of sacrifice and redemption that permeated my environment.

I remember learning about Hossein Fahmideh around the same time. He was just thirteen when he strapped grenades to himself and threw himself under an enemy tank during the Iran-Iraq War. His story was told everywhere—in schoolbooks, on television, in speeches. The message was clear: even a child could be a hero if they sacrificed everything for the nation. Hossein was immortalized, his name synonymous with bravery and devotion. For a child like me, his story wasn’t just history; it was an expectation. Heroes, I was told, didn’t hesitate. They died so the Islamic regime and mullahs could live. Hossein’s legacy, like the posters of martyrs on our streets, made Robin Hood’s imagined death feel like a logical conclusion.

In a sense, my belief that Robin Hood died reflected a child’s processing of the societal expectations around martyrdom. I connected his sacrifice to the idealized figures celebrated in my world—the war martyrs, the men on the news, the stories whispered in hushed tones. Even though Robin Hood wasn’t from my culture, his story resonated with the underlying themes of sacrifice and redemption that permeated my environment.

But maybe that’s why I loved Robin Hood so much. He wasn’t just a tragic hero. He was the hero I needed: flawed, brave, and, for once, alive. Even if, for years, I thought he had died like all the others. My eventual realization that Robin Hood didn’t die was a subtle rebellion against the narrative of martyrdom. It was a moment of dissonance—a hero who lived, defying the expectations drilled into me. This realization mirrored my growing awareness of the contradictions in my society: a world that glorified and demanded sacrifice so the ideas of the regime could live on.

Robin Hood’s “death” fit perfectly into the paradoxes I was already starting to notice about life. Inside our home, the world was warm, hopeful, and filled with the smells of Maman’s cooking. Outside, it was harder, colder, and brimming with contradictions. The same society that celebrated sacrifice also punished individuality. The same streets that honoured fallen heroes were policed by men who shouted at Maman if her scarf slipped too far back.

In hindsight, the cultural elevation of martyrdom explains why I, as a child, instinctively saw Robin Hood as a tragic hero. Yet, his survival introduced a glimmer of a different possibility: that a hero’s worth didn’t have to be measured by their death. This small but profound shift foreshadowed a deeper questioning of the narratives I’d been taught—an early, flickering resistance to the rigid expectations of my world.

Martyrdom was not simply about dying for a cause but was also a form of ideological purification. The martyr was elevated to a heroic status, often serving as a symbol of ultimate loyalty and devotion to the leader, the nation, or the movement. This concept was key in promoting the image of the Islamic Republic of Iran just as in other Fascist states: a world in which individuals were expected to sacrifice their personal identities and lives for the greater good of the state. Let’s take this opportunity to look at Fascism. In fascist Italy, under Benito Mussolini, martyrdom was often linked to the idea of sacrificio — sacrifice for the state and for the leader. Mussolini’s vision of the fascist state was one in which individuals were subordinate to the collective good, and the glorification of martyrdom was one way of fostering this collective spirit. Martyrs were not just those who died for the fascist cause; they were also symbols of the purity and strength of the regime. Martyrdom, in this sense, was not a passive suffering but an active, heroic act that exemplified the values of the regime. Similarly, in Nazi Germany, martyrdom played a crucial role in the cult of the Führer. Adolf Hitler’s regime sought to create a mythical narrative of sacrifice and heroism. The Nazis glorified martyrs who had died for the “racial” and national cause, presenting them as symbols of the purity and nobility of the Aryan race. The martyr, in this sense, was an idealized figure who transcended the individual and became an embodiment of the collective will of the people. The concept of martyrdom was also instrumental in Nazi propaganda, particularly in the efforts to convince the German people of the righteousness of their cause and the ultimate necessity of sacrifice for the survival of the nation.

The glorification of sacrifice in fascism and Nazism went beyond the individual and extended to a broader cultural and political phenomenon. In these regimes, the idea of sacrifice was used to justify a wide range of policies, from military expansionism to the oppression and extermination of perceived enemies. The glorification of sacrifice was not merely a tool for rallying support for war but was also a means of consolidating power and maintaining control over the population.

In fascist Italy, Mussolini’s regime used the idea of sacrifice as a way to inspire loyalty and discipline within the Italian people. The Italian Fascist Party sought to create a new Italian identity, one that was steeped in the values of duty, sacrifice, and loyalty to the nation. Mussolini’s speeches and writings often invoked the idea of sacrifice, urging Italians to give up their individual desires for the good of the state. The concept of the sacrifizio personale — personal sacrifice — was central to the creation of the fascist identity, and the state sought to glorify and honor those who made the ultimate sacrifice for the cause. This glorification of sacrifice was reinforced by symbols, such as the fasces, and by the use of propaganda, which depicted martyrs as heroic figures who had given their lives for the greater good, just like in the Islamic regime of Iran.

In Nazi Germany, the glorification of sacrifice was equally pervasive. The Nazi Party used propaganda to create a cult of sacrifice that exalted the soldier and the citizen who gave their life for the state. The idea of Ehrenmord — the honor of dying for the Führer — was central to the Nazi worldview, and martyrs who died in the name of National Socialism were celebrated as the highest form of human achievement. This glorification of sacrifice was used to justify the horrors of the Second World War, as well as the systematic extermination of millions of people. The idea that death in the service of the Reich was noble and necessary was deeply embedded in Nazi ideology, and it played a crucial role in motivating soldiers and civilians alike to join in the war and to support the regime’s goals.

The glorification of sacrifice was also central to the creation of the Nazi myth of the “heroic struggle.” The idea of struggle, particularly the struggle for the survival of the Aryan race, was at the heart of Nazi ideology. This struggle was framed as a battle of life and death, and the sacrifices made in this struggle were glorified as heroic acts of selflessness. The image of the fallen soldier or martyr became a powerful symbol in Nazi propaganda, serving to remind the German people of their duty to the nation and to the Führer. The glorification of sacrifice was used to justify the brutal and genocidal policies of the Nazi regime, as the death of millions of “undesirable” individuals was framed as a necessary sacrifice for the survival of the “master race.”

The glorification of martyrdom and sacrifice in fascism and Nazism had profound effects on the societies that embraced these ideologies. In both Italy and Germany, the emphasis on sacrifice helped to forge a sense of unity and purpose among the population, but it also led to extreme forms of obedience and repression. By glorifying sacrifice, fascist and Nazi regimes were able to manipulate the emotions and actions of their citizens, convincing them that their loyalty and devotion to the state were of the highest moral value.

In Italy, the cult of martyrdom and sacrifice helped to consolidate Mussolini’s power and to maintain control over the Italian population. The Fascist Party created a culture in which individuals were expected to subordinate their personal desires to the needs of the state, and the glorification of martyrdom helped to reinforce this message. The idea of sacrificio became synonymous with loyalty to the regime, and those who made the ultimate sacrifice were hailed as heroes. This culture of sacrifice created a society in which dissent was virtually impossible, as the ideals of the state were so deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness.

In Nazi Germany, the impact of martyrdom and sacrifice was even more profound. The glorification of sacrifice helped to create a totalitarian state in which individuals were willing to sacrifice their lives for the Führer and the Reich. The Nazi regime used the idea of martyrdom to justify the most horrific acts of violence and cruelty, from the invasion of neighboring countries to the systematic genocide of Jews, Roma, and other minority groups. The idea that sacrifice was necessary for the survival of the nation created a culture in which the individual was disposable, and loyalty to the state was paramount.

The martyrdom of soldiers, civilians, and even children was used to create a powerful narrative of heroism and selflessness. This narrative helped to justify the immense suffering caused by the war and the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime. The cult of martyrdom became a key element of Nazi propaganda, and it was used to rally the population behind the war effort and to maintain morale in the face of defeat. The image of the fallen martyr, whether it was a soldier on the battlefield or a civilian in the streets, became a symbol of the Nazi ideal: a world in which sacrifice for the state was the highest form of virtue.

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, martyrdom is a deeply ingrained part of the state’s political and religious ideology. Martyrdom is a cult in Iran. The concept of martyrdom in Iran is heavily influenced by Shia Islam, which has its own historical narrative of sacrifice, most notably the martyrdom of Imam Hussein in the Battle of Karbala.The martyrdom of Ali and Husayn has had a profound impact on the culture and identity of the Shia Muslim world. The cult of martyrdom in Iran has deep historical roots, dating back to the early centuries of Islam. However, the political and social context of the 20th and 21st centuries has significantly shaped the way martyrdom is understood, commemorated, and utilized in Iran. This narrative is central to Shia identity and is used by the Iranian regime to construct a sense of national and religious duty. The regime encourages its citizens, particularly the youth, to view martyrdom as an honorable and sacred duty, especially in the context of defending the Islamic Republic.

Khomeini’s leadership was rooted in a vision of political Islam that emphasized the centrality of the Shia Imams and their sacrifices for the cause of justice. Khomeini drew on the martyrdom of Ali and Husayn to legitimize the revolutionary struggle against the Shah’s regime, which was seen as corrupt and oppressive. In this context, the martyrdom of Husayn and other Shia figures was framed as a symbol of the revolutionary struggle against tyranny, with Khomeini positioning himself as a modern-day figure akin to Husayn, resisting the oppressive forces of imperialism and dictatorship.

The Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) was a pivotal moment in the institutionalization of martyrdom. The war, which resulted in a massive loss of life, became a defining event for the Islamic Republic. The regime elevated the idea of sacrifice to the level of national pride, encouraging young Iranians to join the military and fight with the promise of martyrdom as the highest honor. The use of child soldiers, especially in the “Basij” militia, was a tragic manifestation of this glorification. Martyrdom in Iran is framed not only as a personal act of devotion to God but also as a contribution to the survival and strength of the Islamic Republic, particularly in its confrontation with external enemies and internal dissent.

The Iranian state also uses martyrdom as a tool for ideological and political legitimacy, particularly in its foreign policy. Iran’s involvement in regional conflicts, such as in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, is often framed in terms of defending the legacy of the martyrs of Karbala. The Iranian government encourages its allies, particularly Hezbollah in Lebanon, to adopt the mantle of martyrdom in their struggle against perceived imperialist forces, particularly the United States and Israel.

The cult of martyrdom has played a significant role in shaping contemporary Iranian politics. Martyrdom is used not only to rally the Iranian population behind the regime but also to justify Iran’s ideological stance on issues such as resistance to Western influence, support for Islamic revolutions, and the defense of Shia communities across the Middle East. Martyrdom is framed as a sacred duty, a means of securing both spiritual salvation and national dignity.

One of the most significant ways in which martyrdom is politicized is through the framing of the Iran-Iraq War as a heroic struggle in defense of the Islamic Revolution. Martyrdom in this context is seen as a defense of the principles of the revolution and the protection of the Islamic state against foreign aggression. The war’s martyrs are elevated to the status of national heroes, and their sacrifice is depicted as a key element of Iran’s resistance to external threats.

In modern Iran, martyrdom is not only a theological or cultural concept but also a powerful political tool. It is used to rally the public around the leadership, to mobilize support for the state’s policies, and to maintain the revolutionary fervor that marked the early days of the Islamic Republic. The political use of martyrdom is evident in the regime’s framing of its conflicts, particularly with the United States and its allies, as a continuation of the struggle for justice and resistance to oppression initiated by Husayn and his companions.

While the religious context in Iran differs from the secular ideologies of fascism and Nazism, there are several key similarities in the way martyrdom and sacrifice are used as tools of political control and propaganda.

- Glorification of Death for a Higher Cause: In all three regimes, martyrdom is portrayed as the ultimate act of devotion, whether to God, the state, or the leader. The martyr is not merely an individual who dies but becomes a symbol of a greater cause. In Iran, martyrdom is tied to the defense of Islam and the Islamic Republic, with the martyr elevated to the status of a holy figure. In fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the martyr is a symbol of loyalty to the state and the racial or national ideal. In all three contexts, death is sanctified, and the sacrifice is seen as both a personal honor and a societal obligation.

- Mobilization of the Masses: Martyrdom is used as a powerful tool to mobilize the population, particularly the youth. In Iran, young Iranians were encouraged to become martyrs during the Iran-Iraq War, with the regime providing incentives such as images of martyrs’ faces on banners and posters. The Iranian government also created a strong institutional framework to honor martyrs, including museums, monuments, and ceremonies, ensuring that the sacrifice was remembered and revered. Similarly, Mussolini and Hitler used the cult of the martyr to inspire the masses, particularly soldiers and young people, to fight and sacrifice for the greater good of the state.

- Sacrifice as a Means of National Unity: In all three ideologies, the concept of sacrifice serves as a unifying force. In Iran, the idea of martyrdom is closely linked to the notion of national and religious unity, particularly in the context of defending the Islamic Republic against perceived threats. The notion of jihad (struggle) in Iran, particularly during the war with Iraq, was deeply tied to the idea of sacrifice for the nation and religion. Similarly, in fascism and Nazism, the glorification of sacrifice reinforced nationalistic and racist ideologies, creating a sense of collective purpose that transcended individual interests. The sacrifice of life for the nation, the state, or the leader was depicted as an honorable and noble act, contributing to the sense of unity and shared destiny.

- Dehumanization of the Enemy: The glorification of martyrdom in these regimes often went hand in hand with the dehumanization of the enemy. In Nazi Germany, the glorification of sacrifice was used to justify the violent subjugation and extermination of racial enemies, particularly Jews, Roma, and Slavs. The Nazis framed the deaths of their own soldiers and civilians as necessary sacrifices for the survival of the Aryan race, while presenting the deaths of their enemies as justified in the name of racial purity. In Iran, martyrdom was also framed as a defense against external enemies, particularly the West and its perceived imperialist ambitions. The Iranian government has used the idea of martyrdom in its ideological struggle against the United States and other Western powers, presenting these sacrifices as necessary for the survival of the Islamic Republic and its values.

- Totalitarian Control and the Cult of the Leader: In both fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, the concept of martyrdom was closely tied to the cult of the leader. Mussolini and Hitler were both seen as infallible leaders, and the martyr’s sacrifice was often framed as a demonstration of loyalty to the leader. In Iran, the martyrdom of individuals is also tied to loyalty to the supreme leader, who is seen as the representative of God on Earth. The cult of martyrdom serves to reinforce the authority of the leader, ensuring that the population remains committed to the regime’s values and goals.

Leave a comment